Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion

Born in 1571, Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer. He is best known for his laws of planetary motion, which he derived from the observations of the Danish astronomer, Tycho Brahe. These laws are as follows:

The Law of Orbits

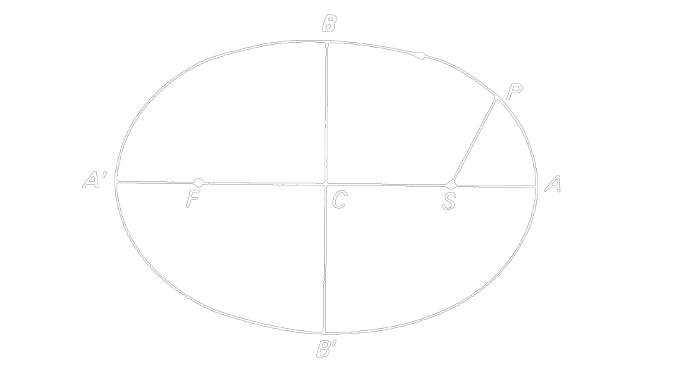

“All the planets revolve around the sun in elliptical orbits having the sun at one of the focii.”

The point at which the planet is close to the sun is known as perihelion, and the point at which the planet is farthest from the sun is known as aphelion. The eccentricity of the ellipse is given by:

\[\begin{equation} e_p = \frac{c_p}{a_p} = \frac{\sqrt{a_p^2 - b_p^2}}{a_p} \end{equation}\]where

- \(e_p\) is the eccentricity of the orbit of the planet

- \(c_p\) is the distance from the center of the orbit to the focus (i.e. the Sun)

- \(a_p\) is the semi-major axis of the orbit

- \(b_p\) is the semi-minor axis of the orbit

The eccentricity of a perfect circle is 0 whereas the eccentricity of a parabola is 1. The eccentricity of an ellipse is between 0 and 1. The eccentricity of a planet’s orbit is a measure of how circular the orbit is. The more circular the orbit, the smaller the eccentricity, and vice versa.

The Law of Equal Areas

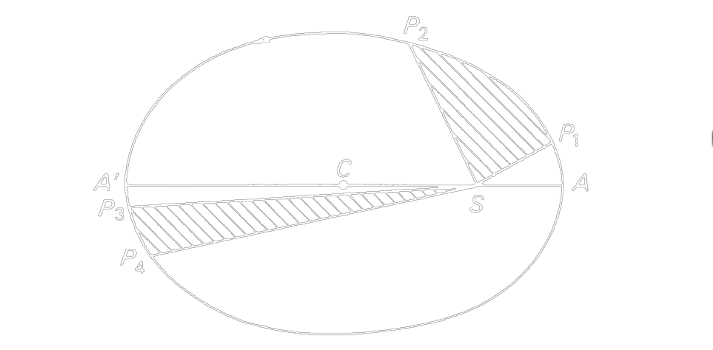

“A radius vector joining any planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal lengths of time.”

Planets don’t move with equal speeds along their orbits. Rather, their speed varies so that the line the line joining the centres of the Sun and the planet sweeps out equal parts of an area in equal times.

This is because as the orbit is not circular, the planet’s kinetic energy is not constant in its path. It has more kinetic energy and hence, more velocity, near the perihelion and less kinetic energy and consequently, less velocity, near the aphelion.

The Law of Equal Areas can be verified using the law of conservation of angular momentum. At any point of time, the angular momentum of the planet around the focii of its orbit (a.k.a. the Sun) can be given as:

\[\begin{equation} L_p = m_pr_p^2\omega_p \end{equation}\]where

- \(m_p\) is the mass of the planet

- \(r_p\) is the instantaneous distance of the planet from the Sun

- \(w_p\) is the instantaneous angular speed of the planet as seen from the Sun

Now, consider a small area, \(dA_p\), described in a short time interval, \(dt\) and the covered angle is \(d\theta\). Then, the length of the arc covered = \(r_p d\theta\).

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} dA_p &= \frac{1}{2} r_p (r_p d\theta) = \frac{1}{2} r_p^2d\theta \\ \Rightarrow \frac{dA_p}{dt} &= r_p^2 \frac{d\theta}{dt} \\ &= r_p^2 \omega_p \\ &= \frac{L_p}{2m_p} \end{split} \end{equation}\]Now, by the law of conservation of angular momentum, \(L\) is constant. Hence, \(dA_p/dt\) is constant. Thus, the area swept out in equal intervals of time is a constant.

A corollary of the law of equal areas, or Kepler’s second law, is that the areal velocity of a planet revolving around the Sun in elliptical orbit remains constant. This implies that the angular momentum of a planet remains constant.

The Law of Periods

“The squares of sidereal periods (of revolution) of the planets are directly proportional to the cubes of their mean distances from the Sun.”

This means that the farther a planet is from the Sun, the longer it takes to complete a single orbit around the Sun. Mathematically, it can be expressed as:

\[\begin{equation} T_p^2 \propto a_p^2 \end{equation}\]where:

- \(T_p\) is the time it takes for the planet to complete a single orbit around the sun

Using the equations and laws of Newtonian gravity, the law of periods takes a more general form:

\[\begin{equation} T_p^2 = \frac{4\pi^2}{G(m_s+m_p)} a_p^3 \end{equation}\]where:

- \(G\) is the gravitational constant

- \(m_s\) is the mass of the Sun

The orbital period of a planet is generally measured in years, and the semi-major axis of a planet’s orbit is measured in Astronomical Units (AU). One astronomical unit is equal to the average distance between the Earth and the Sun, which is approximately 150 million kilometers.

The evidence that the law of periods is indeed correct can be seen from the following data:

| Planet | \(T_p\) (in years) | \(a_p\) (in AU) | \(T_P^2\) (in years\(^2\)) | \(a^3\) (in AU\(^3\)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.241 | 0.387 | 0.058 | 0.057 |

| Venus | 0.615 | 0.723 | 0.379 | 0.380 |

| Earth | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Mars | 1.881 | 1.524 | 3.542 | 3.544 |

| Jupiter | 11.862 | 5.203 | 140.971 | 140.971 |

| Saturn | 29.457 | 9.537 | 866.409 | 866.409 |

Applications

Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion have widespread applications in astrophysics and celestial mechanics. Not only for planetary motion, these laws can be used in any two body system with one object revolving around the other, for example, a satellite revolving around the Earth. In that case, the point where the satellite is closest to Earth is called perigee and the point where the satellite is farthest from Earth is called apogee.