Hohmann Transfer

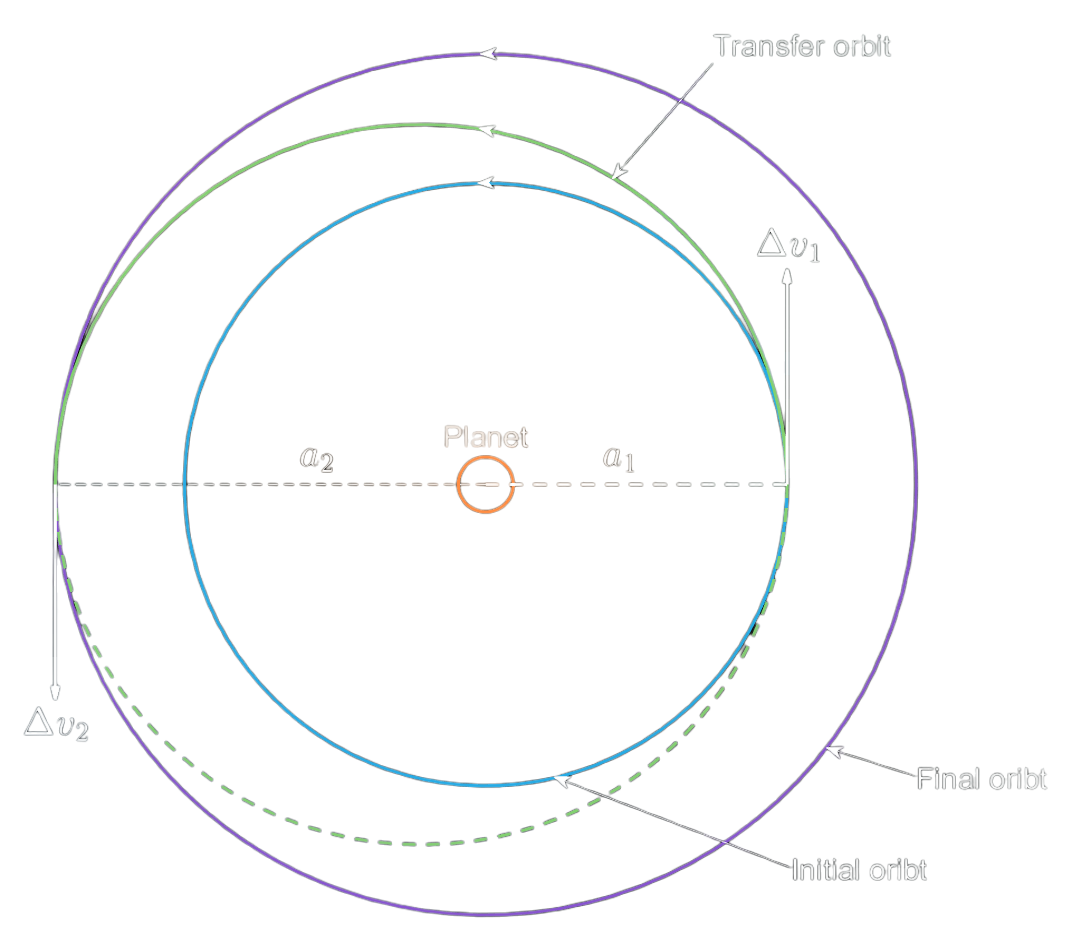

Let’s assume there is a satellite in orbit around Earth at a radial distance \(a_1\) from the center of the Earth and we want to transfer it to an orbit with a larger radius, \(a_2\).

In 1825, Walter Hohmann showed that the most efficient way to do this is to use a two-impulse transfer, when the initial and final orbits are circular and coplanar, is to connect opposite sides of the initial and target orbits with an ellipse. This transfer is called a Hohmann transfer.

The two maneuvers involved in the transfer are:

- The first maneuver at the tangent point of the inital orbit (the first transfer point) places the spacecraft on the elliptic transfer orbit.

- The second maneuver at the tangent point of the final orbit (the second transfer point) inserts the spacecraft into this orbit.

The transfer angle, i.e. the angle between the position vector of the spacecraft at the two transfer points w.r.t. the planet, is 180 degrees. Because the transfer ellipse is tangential, the required velocity change (\(\Delta v\)) at the transfer points is the difference between the circular orbital speed and the velocity on the elliptic transfer orbit at the transfer points. The direction of the \(\Delta v\) is the tangent at the transfer point.

The semi-major axis of the transfer orbit is given by:

\[\begin{equation} a_T = \frac{(a_1 + a_2)}{2} \end{equation}\]The velocity magnitude at any given point on the initial circular orbit is given by:

\[\begin{equation} v_1 = \sqrt{\frac{G M_e}{a_1}} \end{equation}\]where:

- \(G\) is the gravitational constant

- \(M_e\) is the mass of the Earth

The velocity on the transfer orbit at the first transfer point is derived from the following energy equation:

\[\begin{equation} \frac{v_{T,1}^2}{2} - \frac{G M_e}{a_1} = - \frac{G M_e}{2 a_T} \end{equation}\]where

- \(v_{T,1}\) is the velocity on the transfer orbit at the first transfer point

Therefore,

\[\begin{equation} v_{T,1} = \sqrt{2 G M_e \left( \frac{1}{a_1} - \frac{1}{2 a_T} \right)} \end{equation}\]Consequently, the \(\Delta v_1\) at the first transfer point is given by:

\[\begin{equation} \Delta v_1 = v_{T,1} - v_1 \end{equation}\]The direction of \(\Delta v_1\) is the tangent at the first transfer point on the initial orbit, as illustrated above. Similarly, the \(\Delta v_2\) at the second transfer point can be calculated as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} v_2 &= \sqrt{\frac{G M_e}{a_2}} \\ v_{T,2} &= \sqrt{2 G M_e \left( \frac{1}{a_2} - \frac{1}{2 a_T} \right)} \\ \Rightarrow \Delta v_2 &= v_2 - v_{T,2} \end{split} \end{equation}\]As before, the direction of \(\Delta v_2\) is the tangent at the second transfer point on the final orbit. The time taken to coast from the first transfer point to the second (transfer duration) is half the orbital period of the transfer orbit. Hence, from the law of periods,

\[\begin{equation} t_T = \pi \sqrt{\frac{a_T^3}{G M_e}} \end{equation}\]